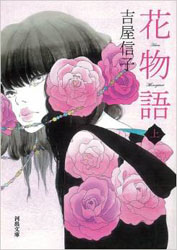

If I bothered to make New Year’s Resolutions at all, my one resolution for 2016 would have been that the first Japanese novel I completed would be Yoshiya Nobuko’s Hana Monogatari, Part 1 (花物語 上). It was, for most of the 20th century, the definitive collection of girl’s literature in Japan, as Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series was in the 20th century for American girls, and as The Babysitters Club is to people younger than I am. ^_^ It is also considered by many people to contain early proto-Yuri work.

If I bothered to make New Year’s Resolutions at all, my one resolution for 2016 would have been that the first Japanese novel I completed would be Yoshiya Nobuko’s Hana Monogatari, Part 1 (花物語 上). It was, for most of the 20th century, the definitive collection of girl’s literature in Japan, as Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series was in the 20th century for American girls, and as The Babysitters Club is to people younger than I am. ^_^ It is also considered by many people to contain early proto-Yuri work.

And so, after many days of diligently plowing through some amazing – and some amazingly awful – stories, I have fulfilled that non-existent resolution. ^_^

Hana Monogatari, “Flower Tales,” were originally serialized in girl’s magazine Shoujo Gahou from 1916-1924. Each story is named after, and sometimes refers in the story, to a specific flower. The stories follow young women in their teens and early twenties, most often in school, but sometimes as they strike out into adulthood.

The first part of the collection begins with a ribbon story – that is, a scenario that is meant to tie the stories together. In this case, it is a number of middle-aged women, sitting together and reminiscing about their youth. The first dozen or so stories are presented as a flashback, but about midway through the volume, the ribbon story slowly fades and we’re left with a remarkable collection of stories about girls and young women, written by a young woman in Japan in the 1920s.

I’m not going to summarize every story. I honestly couldn’t, simply because there were some where my comprehension was tenuous, to say the least. And I’m kind of on the side of grumpy old folks who say Japanese kids’ reading comprehension has gone down, if this was what was popular with middle school kids in the 1920s! Compare this to most Light Novels being published for adult otaku and Hana Monogatari is practically college-level reading. ^_^;

After reading a number of stories, I started taking notes when a piece really stood out. The first such story was “Cosmos,” sometimes noted as a clearly proto-Yuri story. I’d disagree with that, but that’s an argument for another time. Cosmos is made up of a girl’s letters to her onee-sama as her mother is in the hospital, ending with her mother dying and the girl having to leave school forever. My note says only “Brutal.” It’s not the only one. Death is a common factor in many of the pieces. The worst of these often had a red shirt on the character from the get-go, such as the younger brother in “Tsuriganesou.” It was instantly obvious the kid was gonna die, but still, the news was presented without a hint of feeling or compassion and I actually flinched when the neglectful uncle bothered to tell his sister. “Ah, um, so…he’s dead.”

“Shiroyuri” was sweet and hopeful, while “Fukujusou” is one of the few stories with what can be considered a “happy ending” when a girl who was parted from her onee-sama meets her again as a young adult.

“Hinageshi” started really beautifully, with two girls meeting at school, dancing in a patch of red poppies flowers and talking while in the rocking chairs in the waiting room, but ended up rather emptily.

“Himomo” was a strange little tale of a girl who is giving and kind, so of course the other girls make fun of her for her sense of responsibility. She has a habit of taking care of what we might think of as a lost and found box. In it, she finds a little set of bookshelves, with lovely letter from a teacher who had to leave the school. I believe this was the first story I read that did not end in a melancholy fashion.

The first story with anything approaching what I would consider to be Yuri, was “Tsuyukusa.” Akitsu and Ryouko love each other, they “yearn” for each other. When they are parted it is harsh and abrupt – and rather cruel on Ryouko’s part. I immediately note the use of the name “Akitsu” – the same name given to one of the protagonists of Yaneura no Nishojo. I wonder who Akitsu was, and what she meant to Yoshiya-sensei. ^_^

“Benibara, Shirobara” was a sweet story that was sweet without melancholy. With the Red Rose/White Rose contrast, I of course saw the kernel of the Rosas of Lillian Academy. ^_^

There were two stories that were really the standouts for me. Of these, we’ll start with “Dahlia,” as I have already brought up Maria-sama ga Miteru. ^_^ This story follows a woman out of school, Touko. Touko has become a nurse in the town in which she attended school. When a former classmate is admitted to the hospital, the former classmate’s rather wealthy and prominent family asks Touko to be their daughter’s private nurse. The head of the hospital strongly encourages her to do that, as it will be good for her both monetarily and prestige-wise. But that night Touko is on the ward comforting a small child whose mother isn’t there and she realizes that this was why she became a nurse. She rejects the offer in order to help people who really need the comfort and companionship. Shades of Marimite‘s Matsudaira Touko lay heavily over me as I read this story, remembering Touko’s own story of early life in a hospital and the nurses there who were kind to her.

The last story of note was really noteworthy. Called “Moyuruhana,” which Dr. Frederick (the scholar who brought us the superb translation of Yellow Rose from Hana Monogatari, which I reviewed in February 2015) suggested be translated as “Smouldering Flower”. This story was…well, it felt sort of like a vampire story without any vampires. Midori becomes infatuated with “Mrs. Kataoka” a new teacher at school. The use of the English “Mrs.” is emphasized, rather than calling her Kataoka-fujin or -sensei. Midori comes to Mrs. Kataoka’s room one night, where the teacher is described like a “Snow Queen”, pale in the reflected light of the snow outside. Mrs. Kataoka embraces Midori, whispering that young girls like her “are the best.” At this point I read the rest of this story as if it were a kind of Carmilla-esque tale and it worked *perfectly*. Midori becomes increasingly obsessed, but when she tries to see Mrs. Kataoka again, she’s stopped from entering by a mysterious older woman who strokes a black cat (!).

A guy in a black suit arrives to try to pay off the principal, Wagner-sensei (ya see what I mean about Carmilla, yes?), to hand Mrs.Kataoka over, Wagner-sensei tells Mr. Suspicious to bag off, he threatens the school.

The climax of the story is in fine Gothic form as the school buildings go up in flame and neither Mrs. Kataoka nor Midori can be found and both disappear from the story completely. In the final pages, Wagner-sensei suddenly becomes the protagonist of the story by saving the school.

This was so eyebrow-raisingly amazing a story, I couldn’t wait to tell you about it. ^_^

The initial chapters/stories are short, but as her work grew in popularity, clearly she went from shorter stories to longer ones. As a point of contrast early stories run about 6 pages in this edition and the later stories go as long as 30 or more pages.

Color, too, plays a big part in the stories, as one might expect. Frequently the color of a flower is one of it’s significant qualities. Red roses, violets, tiger lily, daisies, and so on, so you can imagine the scene quite spectacularly clearly when I say “a field of red poppies” or “violets in the garden.” The mood of the story is often tied up in the color associated with it. Lavender twilights and melancholy, golden sunshine and daises, that kind of thing.

My admiration for Yoshiya-sensei jumped up by significant amounts reading this book. While many of the stories were tinged with a melancholy, she manages to play around with tone and voice quite a bit – especially as the stories progress.

Ratings:

Overall – 9

This was not an easy read, there were any number of deaths to deal with, but as I read her work, I’m coming to appreciate it more and more. Hana Monogatari deserves it’s status as the definitive example of early 20th century Japanese girls’ literature. I’m really looking forward to getting to Volume 2!

![]() Today I award myself a Yuri History Achievement Badge. I have finished Yoshiya Nobuko’s Hana Monogatari, Part 2 (花物語 下).

Today I award myself a Yuri History Achievement Badge. I have finished Yoshiya Nobuko’s Hana Monogatari, Part 2 (花物語 下).