Post-publishing Addendum: Kalabaw Studios, as we know it, is defunct due to the actions of its former editor-in-chief. The editor-in-chief abused the artists working under them, and we cannot, in good conscience, recommend picking up Silakbo or Silakbo 2 through Shopee or any other channels Kalabaw Studios operated. You can find out more about the situation here. Instead, please support the artists directly. They are trying to reclaim ownership of Silakbo, but until then, do not buy Silakbo or Silakbo 2. Support other Filipino yuri/GL initiatives as well, such as the upcoming anthology Gigil, to be released at Komiket Pride on June 7.

Post-publishing Addendum: Kalabaw Studios, as we know it, is defunct due to the actions of its former editor-in-chief. The editor-in-chief abused the artists working under them, and we cannot, in good conscience, recommend picking up Silakbo or Silakbo 2 through Shopee or any other channels Kalabaw Studios operated. You can find out more about the situation here. Instead, please support the artists directly. They are trying to reclaim ownership of Silakbo, but until then, do not buy Silakbo or Silakbo 2. Support other Filipino yuri/GL initiatives as well, such as the upcoming anthology Gigil, to be released at Komiket Pride on June 7.

Hello, this is Miguel Adarlo, an overachieving potato on Discord. I wanted to share a recent yuri anthology released in the Philippines. I shared it over at the Okazu Discord, and then I was allowed to share it with the wider world over Okazu. So, thank you, Okazu and the rest of the Okazu Discord!

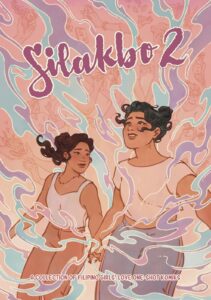

Silakbo 2 (silakbo – frenzy) is a yuri/women-loving-women anthology published by Kalabaw Studios in March 2024. Edited by Logihy, Silakbo 2 contains ten one-shot girls’ love stories in English by queer Filipino artists from all over the country. The previous Silakbo followed this format as well.

As Logihy explains in her Editor’s Note, the theme for this anthology is magic realism, where “ordinary moments become extraordinary” and reality bends to celebrate sapphic love. This theme shines through not only in the stories contained within, but also in the art. Each artist brings their unique voice to the anthology, with styles ranging from soft, painted colors to clear, defined linework. Printed in full color on glossy paper, the anthology further accentuates the artwork, making the colors vibrant.

Beyond the magic realism theme, another powerful undercurrent emerges – kindness. Kindness of all kinds, in this case, that can be considered radical with how it can be applied, as well as who applies it.

The stories are then as follows. Spoilers abound, but as with many anthologies, I think the plot is only part of the experience of reading these stories:

“Touring Back to You” by Hirayel is about Bea traveling to Negros Occidental on a trip of some sort. There, she meets their tour guide, Catalina, who seems familiar to Bea. What follows is then a tour through Negros, passing by places such as Mt. Kanloan, and the Burgos Public Market, as Catalina and Bea bond over local snacks. As they reach the end of their trip at Aguisan Pantalan, revelations are made. It turns out, Catalina was in a deep and loving relationship with Bea, but due to a mishap in her memory alchemy, Bea forgot about her. With the trip, Catalina has a chance to redeem herself and return Bea’s memories, and hopefully, her relationship with Bea. Catalina’s plan worked, but it worked more than she imagined.

While the central conflict of the story might be foreseeable – the amnesia trope is a familiar one – the sweetness of Touring Back to You lies in its execution. The art, as mentioned earlier, plays a significant role. The idyllic landscapes and bustling markets of Negros become more than just backdrops; they transform into catalysts for Bea’s memory retrieval. Each shared glance at Mt. Kanloan, each bite of a local delicacy from the Burgos Public Market, could potentially be a missing puzzle piece for Bea. This creates a beautiful tension for the reader – we, alongside Catalina, wait with bated breath for a spark of recognition to flicker in Bea’s eyes. The telegraphed plot point of Bea’s amnesia, therefore, becomes a source of emotional investment, rather than a detriment to the story.

“Homemaker” by Eleidoscope follows Renata’s mother, who’s having a hard time connecting to her daughter. Her daughter wants to leave the nest and is growing ever further distant from her mom. One of Renata’s mom’s friends was speculating that Renata has a boyfriend, but Renata’s mom knows that her daughter doesn’t have a boyfriend, but a girlfriend. Whatever the reason is, Renata’s mom just wants to be a part of her daughter’s life. A chance encounter in the house brought about by a broken spoon led to a chain of events that ended with the family closer together, from Renata’s mom teaching Renata how to cook the family’s arroz caldo (rice broth – think rice porridge with chicken,) to even meeting Renata’s girlfriend, Jackie, and accepting her into the family.

The “cute and whimsical” art style in Homemaker isn’t just aesthetically pleasing; it serves a deeper purpose. The hand-painted quality imbues the comic with a sense of warmth and personal touch, reflecting the love and support within Renata’s family. This is further emphasized by the focus on everyday domestic scenes – the kitchen where they cook arroz caldo, or simply the house they share in all its pastel colors. Eleidoscope’s “hugot” (deep emotional experience) aligns perfectly with this visual storytelling. Their depiction of “being queer at home, and having the safe space to be known and to be true to myself” resonates through the art. There was a sticker made by Eleidoscope that came with Silakbo 2 that said, “Nanay approved kabadingan” (mom approved gayness/queerness). This sticker encapsulates the message this story wants to tell, that of acceptance by one’s family.

“Alas tres” (Three O’clock) by Denimcatfish and Samantingsodium is about Nat and the world she sees in the mirror. Nat feels listless as she moves into a new home with a strange mirror inside. As the clock strikes three, however, a girl appears in the mirror named Maya. For the next hour, Nat and Maya converse with each other, not with spoken language, but with drawings and whatever she can write down on paper. This continues throughout, and Nat doesn’t feel as listless anymore. She looks forward to the time she spends with Maya. One day, though, Maya motions to Nat to try something else. They put their hands together on the mirror, and then both are whisked away to an unknown space. In this unknown space, they then can truly meet and feel each other, with no mirror blocking them.

The art style in Alas tres goes beyond simply being visually appealing, as the use of distinct colors plays a critical role in depicting the separation between Nat’s world and the world behind the mirror. While Maya’s world might not be as vibrantly colored as one might expect for a fantasy realm, it uses a different color palette compared to Nat’s. The muted blue colors in Nat’s world could symbolize her initial listlessness, while the contrasting orange tones in Maya’s world represent a different kind of energy or atmosphere from Nat’s world. This distinction emphasizes the separation between their realities. A clear shift occurs during their transition into the unknown space – the colors change and bloom as they break free of the mirror’s barrier and enter the unknown space together. The final burst of color, where both Nat’s blue and Maya’s orange meld together to form a bright, saturated picture, signifies the culmination of their desire for connection, a powerful emotional payoff for the reader who has accompanied them on this journey.

“Sleep Talk” by Zepra deals with AJ and her dreams. Within her dreams, she is the master of her realm, being able to control all aspects of it. That is, until one day, her classmate Ela (short for Mikaela) appears. The day after, AJ meets Ela at school and confirms that Ela was visiting AJ’s dreams. From there on, in AJ’s dream world, they go on adventures together, but in the real world, they don’t interact as much, though they do become targets of gossip. AJ is content for their status quo to continue, but one night, Ela decides to confess something to AJ, but her words blur out as AJ falls out of her dream. The point-of-view then switches to Ela. In the real world at school, since AJ fell out of her dream, AJ has been avoiding her, at least until she finds a note in her bag. The note’s from AJ, and it’s telling Ela to meet her at 3 pm over at the roof deck. There, it turns out AJ did hear what Ela said and is ready to give her response.

As Zepra mentions in the author’s note, Sleep Talk explores the concept of finding comfort in a small, self-contained world. AJ’s dream realm represents this perfectly. Here, she’s the architect of her reality, free from anxieties and insecurities. However, the story goes beyond simply depicting a comfortable dream world, as Zepra emphasizes the importance of venturing out of this safe space. The note AJ leaves for Ela signifies this crucial step. It takes courage to bridge the gap between the dream world, where everything is under control, and the real world, where things are uncertain. The details in the story, from the characters’ body language to their internal thoughts, showcase the emotional journey of taking this leap. We see the hesitation in AJ’s initial avoidance, but also the bravery it takes for her to reach out again. Sleep Talk, even as a one-shot, leaves a lasting impression by portraying this relatable human experience – the comfort of a self-contained world and the courage required to step outside of it.

“Kismet in My Mind” (art by Hasukeii and story by Ravenndei) centers on Carol. Carol could hear the thoughts of the people around her since childhood, and she got into trouble with one of her friends because of it. She thus keeps her ability to herself, but this one particular day, on the train she’s on, she hears the thoughts of one girl. This girl is checking Carol out, and she thinks Carol is “cute and pretty,” and she’s having some sort of screaming fit in her mind. It turns out, though, that both she and Carol are headed to the same place for the same function, a social event for women-loving women at a bar in Kamuning. There, Carol still can hear the girl’s (whose name was revealed to be Kit) thoughts. How was it that they were on the same train and they were going to the same event? A further game by the events’ organizers then pairs them up, where Kit’s thoughts go into overdrive, thinking that Carol’s prettier up-close, how she hopes she doesn’t look weird, and how much she wants to kiss Carol. Carol happens to hear all those thoughts and decides to finally answer Kit’s thoughts.

Kismet in My Mind offers a delightful meet-cute at its core, but the story’s true depth lies in its exploration of identity and connection. Carol’s ability to hear thoughts acts as a powerful allegory for the queer experience. Just as Carol feels ostracized for being different, LGBTQ+ individuals can often experience isolation or misunderstanding. However, the story flips this concept on its head. Carol’s ability, instead of being a burden, transforms into a bridge that connects her to Kit, another woman who shares her identity. The art by Hasukeii beautifully complements this theme: The character designs, with their soft lines and expressive features, portray a sense of gentle vulnerability, mirroring Carol’s initial hesitation to embrace her ability. When Kit enters the picture, the art style subtly shifts. Kit’s wide eyes, reminiscent of other yuri artists, depict a mix of excitement and nervousness, perfectly capturing the blossoming feelings between the two characters. This visual language reinforces the story’s message – that queerness is not something to be feared, but a unique quality that can foster connection and belonging within a supportive community, as symbolized by the social event depicted in the story. The “sana all” (”wishing it were true for everyone, especially myself”) sentiment that arises from one of the comments in the story takes on a new dimension – it’s not just about the romantic connection, but also about the joy of finding acceptance and love for who you are, a truth echoed in the tender and hopeful mood of the artwork.

“Paruparong Bukid” (Butterfly from the Field, it’s a folk song) by Prinsomnia features a florist named Violet. At a funeral, she happens to meet a girl named Jeanne. Jeanne so happens to be crying literal butterflies. Violet stays with Jeanne and comforts her until Jeanne calms down. She then offers Jeanne a look at her flowers. Jeanne accepts and grows to have a relationship with Violet. To Jeanne, Violet was the only person to call the butterflies she makes beautiful. With Violet, Jeanne feels safe. This would be a contrast to her parents, who call her a pervert, call her butterflies “disgusting,” and generally denigrate her existence, under the pretense of securing a better future for her. This brings Jeanne to tears, enough that she decides to run away. She appears to run to Violet, with whom she frolics in a field with butterflies.

The brilliance of Paruparong Bukid lies in its masterful use of ambiguity. The story is a tapestry woven with unanswered questions, each one inviting the reader to participate in its creation. The very first scene – a funeral – throws us into the heart of Jeanne’s emotional turmoil. Whose funeral is it? Was it a loved one, deepening her despair, or a distant relative, emphasizing her isolation within her family? This ambiguity allows us to connect with the story on a personal level, inserting our own experiences into the gaps. Prinsomnia’s core message of “radical love and kindness” remains the brightest thread in this tapestry. Violet’s love and acceptance of Jeanne’s butterfly tears, a symbol of her pain and ostracization, stands in stark contrast to the judgment Jeanne faces at home. The story doesn’t answer whether Jeanne runs away seeking solace with Violet or finds a more permanent escape. This open-endedness allows the themes of acceptance and the transformative power of kindness to resonate even more powerfully. Even in the face of unspoken trauma and a confusing situation, Violet’s actions offer a beacon of hope, a testament to the power of empathy in a world that can be cruel and unwelcoming.

“One in One Thousand” by Logihy explores the life of Jackie, a hardworking executive who has a bit of a temper, and regularly talks down on her workers. Jackie seems to have it all, but her relationship with her girlfriend, Elaine, is on the rocks, with Jackie feeling that Elaine’s distant from her. One morning, though, Jackie feels an electric shock while touching Elaine’s hand. She doesn’t feel an electric shock with her subordinates though. She wonders why she was shocked by Elaine but not anyone else, and she concludes that this was some sort of divine punishment for her mean attitude. To her, not being able to hold her most beloved in her arms is the most severe punishment there is, so she decides to work on her attitude, becoming kinder in the process. It didn’t work, but Elaine revealed the reason why she felt distant. She didn’t want to burden Jackie on top of the work Jackie was already doing. With that miscommunication out of the way, they profess their love for each other, and suddenly, Jackie can touch Elaine again without risking a shock.

Logihy’s art style in One in One Thousand is undeniably striking. The confident lines and polished presentation create a visually appealing experience, but this aesthetic goes beyond mere surface-level charm. The bold lines and sharp angles can be interpreted as a reflection of Jackie’s initial demeanor – sharp, assertive, and perhaps even a little cold. This is especially evident in scenes where she interacts with her subordinates. The electric shock Jackie experiences when touching Elaine becomes a striking symbol of the emotional barrier between them. The inability to touch due to the electric current reinforces this disconnect. However, the art style shines most in its ability to tell the story through visual elements. Even without a stylistic shift, the way Jackie and Elaine are depicted in the panels can hint at the growing tenderness and the eventual relief Jackie feels once their problems are resolved and their love is reaffirmed.

“Where the Heart Is” (Story by Momo my and Art by Marc M.) follows Coleen as she hops between universes. At the start, Coleen was waiting for a date, but it turns out, thanks to a reminder from her best friend Rose, she made the date in an alternate universe. She then jumped into an alternate universe where she did make the date, but then, it turns out that in this universe, she dated her best friend Rose. She was about to ask Rose about the details, but then she accidentally jumped into another universe. As she gathered her thoughts, Coleen had a love epiphany of sorts, realizing how close she was with Rose. As she walked around in the universe she fell into, she met Rose, who, it turns out, was going on a date. As she tried to chase after Rose, she tripped and found herself in yet another universe. As things seemed bleak and Coleen felt lost, Rose came in with a blanket. With Rose by her side, Coleen finally feels at home.

While the story’s central message of finding a home with your beloved resonates deeply, it also raises intriguing questions about the characters’ lives in the alternate universes Coleen keeps jumping between. We see Coleen grapple with the consequences of her interdimensional travel – accidentally dating her best friend Rose in one universe, leaving another date hanging, and feeling utterly lost after yet another jump. This raises the question: what about the lives of those left behind in these alternate universes? Does the Rose who went on a date in the universe Coleen landed in ever figure out where her date disappeared to? Does the Coleen who was supposed to meet someone special ever wonder what might have been? Marc M.’s art style, thankfully, provides a welcome contrast to the questions the story raises. There’s also a possibility the color palette used in the work might hold a deeper meaning. It bears a resemblance to the lesbian flag, which, if intentional, adds a subtle layer of appreciation for Coleen and Rose’s relationship. Whether a deliberate choice or not, the art style in Where the Heart Is beautifully complements the story, making it a truly engaging experience.

“Tinned Fish” by Sobsannix delves into the story of Cam, as she has weird dreams where she is turned into a field mouse who is then eaten by a cat. Ever since she started having those dreams, she hasn’t had good sleep. One night, she decides to just let the cat consume her as she falls asleep, leading to her taking control of her dream. She tries to negotiate with the cat to not eat her. It seems like the cat understands her, but then she gets eaten anyway. As Cam wakes up, she realizes that she can bring food into her dreams, and does so the next time she sleeps. The cat takes in the sardine sourdough toast with sweet onions and radishes. The cat likes it and begins to speak. While speaking, the cat turns into a girl, saying that she won’t eat Cam as long as Cam brings food into her dream. Cam then wakes up, and while in the real world, she encounters a familiar smell coming from a lady waiting nearby for the train. Cam didn’t get to confirm if the lady was the same cat from the dream, but she decided to bring some mackerel when she went to sleep. Turns out, the cat, named Coley, is a dream hopper who jumps into dreams. Cam and Coley then share a friendship that leads to something more while in the dream. Coley also admits that she regularly targeted Cam’s dreams, as she “got addicted” to how Cam tastes. Cam wants to meet Coley in real life, but Coley’s unsure, as she doesn’t recognize whoever she forms a bond with. This leads to Cam waking up and trying to find Coley. In the end, Cam finds Coley in the bar with her scent.

Unlike the other stories in the anthology, Tinned Fish boasts a unique brand of “cute.” Sobsannix’s art style is a touch scratchy, yet undeniably endearing. It perfectly captures the dreamlike world Cam dives into, where she shrinks to a mouse and interacts with a peculiar cat named Coley. The character designs for both Cam and Coley are particularly interesting – the scratchy lines add a layer of whimsy that reflects the absurdity of a talking cat who enjoys a good dream-time snack. This aesthetic perfectly aligns with the author’s intention of creating something “cute, love-y, and fun.”

“Everything Out of Reach” by Alamangoes (she also drew the cover art for this anthology) depicts the challenges faced by Soledad (Sol) as she falls in love with her childhood friend, Lara. Sol loved Lara ever since they were children, but in a lollipop, she saw the many ways their friendship go wrong if she were to confess. So she decided to hide her feelings instead. She was scared of Lara hating her, and this fear of the future grew with her. When Sol and Lara were picking college courses, Sol picked a more mundane path with a nearby college, while Lara chose a college far away. Before Lara left though, she confessed to Sol, only for Sol to unspool her anxieties about how the relationship wouldn’t work without even responding to Lara’s confession. Years pass by, and Lara returns home. Sol and Lara hit it off again and reconnect, though there’s always this undercurrent from Lara that things could go wrong. It’s only when Sol and Lara have a heart-to-heart about their futures that things start unraveling from Sol’s end. Sol talks of visions she sees, and how she can see the many futures ahead of her, and yet everything goes badly for her. It’s only when Lara promises a future together that Sol finds it in herself to fall in love and let the pieces fall where they may be, rather than constantly catastrophizing about her future with the visions she sees. As Sol and Lara leave to face the future, Sol pulls out some lollipops. The lollipops show the many ways their future would take fold, such as them staying together or splitting up, but this time, she takes the lollipop hand-in-hand with Lara.

Alamangoes’ art style shines through in its ability to capture the emotional core of Sol’s story. Whether it’s the cover illustration featuring Sol and Lara as adults, brimming with a hopeful nervousness, or the visual representation of Sol’s anxieties, the art perfectly complements the narrative. We see Sol’s fear of rejection reflected in her initial apprehension towards Lara’s confession. Alamangoes cleverly uses lollipops, bubbles, and even literal haze emanating from Sol to depict the overwhelming and sometimes suffocating nature of her visions of alternate futures. Within these objects, Alamangoes draws images that represent the many potential outcomes Sol fixates on – a powerful visual representation of her overthinking. This directly connects to the author’s dedication in the notes – a story for “all the overthinkers and late bloomers out there.” The way Alamangoes depicts Sol and Lara together, particularly amidst Sol’s visual anxieties, offers a powerful message of hope. It resonates with anyone who has ever been paralyzed by fear of the unknown, reminding us that even the most overwhelming anxieties can be overcome, and that true connection can be worth the risk.

While the anthology is billed as magic realism, another powerful theme emerges – radical kindness. This kind of kindness permeates throughout the stories, such as the kindness and understanding that Violet shows Jeanne in Paruparong Bukid, Lara reaching out and reassuring Sol about their future together in Everything Out of Reach, among many other examples throughout the anthology. The authors’ notes offer insightful perspectives on radical kindness, highlighting its importance in creating safe spaces, fostering self-acceptance, and building connections within the LGBTQIA+ community in the Philippines – a community facing legal limitations and societal prejudice. For example, in the Family Code, a marriage is defined as “a permanent special contract union between a man and a woman.” Bills trying to give queer people equal rights languish in Congress with no hope of being passed. Combine that with harmful stereotypes, is it any wonder why the authors express the need for kindness when kindness for them is in short supply?

I’m not as deep into the community as I like, being more of a lurker, but through Silakbo (both anthologies), I’ve come to appreciate the crucial need for safe spaces and equal rights for LGBTQIA+ individuals. Until then, though, we have to practice radical kindness to create a kinder world.

I do hope that by sharing Silakbo with a wider audience, not only those within the Philippines, I can at least spread the stories the artists want to share.

May all your lives be kind and soft (sabi ng mama mo).

Ratings

Art – 10, a feast for the eyes, with the different styles serving to build the narrative, as well as to show off the artists’ preferences, especially with the color choices.

Story – 8, some stories feel like they could be expanded a bit more, or were constrained by the format.

Characters – 8, generally agreeable, though, again, I feel as if I would have wanted to spend more time with them.

Service – 0

Yuri – 10. The anthology encourages you to spread the gay.

Overall – 9

You can reach the publisher of this anthology, Kalabaw Studios, over here. You can buy their anthology, as well as many other works published by them through Shopee.

Thank you Miguel! This is just wonderful. I’m going to put this on my to-get list. ^_^

![]() I came across Iori Kusano’s Hybrid Heart at Flamecon 2025 in New York City. The man at the table pitched it to me, but I was already sold after looking at the cover. This is a story about an idol, Rei, who is the remaining half of a duo, Venus Versus. When her partner Ririko left, she stayed…and is regretting the decision more every day.

I came across Iori Kusano’s Hybrid Heart at Flamecon 2025 in New York City. The man at the table pitched it to me, but I was already sold after looking at the cover. This is a story about an idol, Rei, who is the remaining half of a duo, Venus Versus. When her partner Ririko left, she stayed…and is regretting the decision more every day.