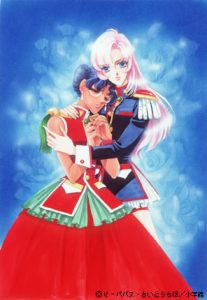

The manga for Shoujo Kakumei Utena premiered in June 1996 in Ciao magazine, Shogakukan’s popular magazine for girl’s manga. The anime followed on in 1997. Both were collaborative efforts with contributions from established manga artist Saitou Chiho and anime director Ikuhara Kunihiko, who was just off of a wildly popular season of Sailor Moon. These two, along with Hasegawa Shinya (animation supervisor for Neon Genesis Evangelion), writer Yōji Enokido, and producer Okuro Yuuichiro, collaborated as a team known as Be-Papas. Both anime and manga were produced simultaneously, but each treated the subject matter differently.

The manga for Shoujo Kakumei Utena premiered in June 1996 in Ciao magazine, Shogakukan’s popular magazine for girl’s manga. The anime followed on in 1997. Both were collaborative efforts with contributions from established manga artist Saitou Chiho and anime director Ikuhara Kunihiko, who was just off of a wildly popular season of Sailor Moon. These two, along with Hasegawa Shinya (animation supervisor for Neon Genesis Evangelion), writer Yōji Enokido, and producer Okuro Yuuichiro, collaborated as a team known as Be-Papas. Both anime and manga were produced simultaneously, but each treated the subject matter differently.

Now seems like a good time to look back at 20 years of Revolutionary Girl Utena.

Tenjou Utena is an idealist. She is a young woman who, like most young women, is looking for her prince. Who that prince is, and how she meets him again, is portrayed variably in every version of the story, but this basic idea is the plot that underlies all versions.

The base plot appeared on the surface to be a relatively straight-forward magical girl formula. A girl who desires to become a prince comes to a elite private school where she duels for the hand of the “Rose Bride.” The series included a magical transformation every week, and a duel for the hand of princess. It even included a comedic animal sidekick. It was clearly a magical girl anime. However.

Utena wasn’t herself magical, like Moon Princess Tsukino Usagi (Sailor Moon) or a magic user like Yumeno Sally (Mahoutsukai Sally). She wasn’t given a magical item that suddenly gave her access to magical powers like Nonohara Himeko (Hime-chan no Ribon) or Hanasaki Momoko (Wedding Peach.) Utena is given (or finds, depending on the iteration) an item, and it does allow her access to a world in which magic exists, but she herself has no way to use the magic of her own volition. Instead, the magic would enter her when it needed to, to achieve an end only vaguely defined as “the power to revolutionize the world.”

When the series was running on Japanese TV and we were talking about it obsessively on the original Anilesbocon Mailing List (which was rendered defunct by Yahoo in 2001) the series was often spoken of as a subversion of a magical girl series. And certainly, one could see it as such. It takes the stock characters of any anime and manga set in a school, layers on a “purpose” that isn’t saving humanity, or making people happy, or even stealing back people’s precious belongings. That purpose is flatly stated to be a “revolution” – although what that meant to the world is never explained.

As we watched the series, there were some qualities that supported the subversion of a magical girl series perspective. In early magical girls anime and manga, the protagonists have simple female gender-role-assigned goals; becoming a princess and marrying a prince primary among them. “Helping people” became “saving the earth” from dastardly baddies in later series. But who was Utena helping in her duels? Who was being saved? This was not your typical magical girl series.

The Elements of a Revolution

The writing in Revolutionary Girl Utena is not unique as such. Many anime use ancient or modern archetypes to populate a story. Anime is especially full of characters who are”types” rather than fully developed. However, the characters that populate Ohtori are not just “glasses guy” or “passive-aggressive girl,” they are, rather the kids you went to school with. (Admittedly, blown well out of proportion.) Kiryuu Touga, the elite athlete who didn’t care about the girls who fawned over him, Saionji Kyouichi the bully with the inferiority complex, Arisugawa Juri the cool girl that everyone loved, but no one could get close to, and Kaoru Miki, the lonely genius. And you. You were the iconoclast. Of course you were. We all were. Doing our own thing, regardless of who liked and didn’t like us.

These are not literary archetypes. They are our archetypes.

And they are tied together by our quest in a kind of fractured fairtyale. We recognize the quest; it is the quest that lies under our own endeavors as young people – to be a hero…to do something noteworthy. Utena is all the things we were and weren’t all at once. She is athletic and geeky and naive and cool and comfortable in her body in ways that we never were. She has the right to enter the duels and she gets to have the magic and the girl, something we probably couldn’t really imagine for ourselves. Not then…maybe not now. But Utena could. She is Sir Gareth, taking on the noble and elite knights, putting up with their taunts and their derision until one day it was they who were challenging her. And losing. And in doing so, it freed them from their own prisons.

The themes of Utena are the same themes of any fairytale. A prince comes to free the princess from her bondage. The prince engages in duels to posses to princess. But, we’re supposed to understand that the rules of fairytales are not entirely applicable. That Utena, a girl, wants to be a “Prince,” i.e., that she wants the agency herself and not be rescued but to be the rescuer is presented as a flipping of the standard. On the cusp of the 21st century, female viewers asked “What’s so amazing about that?” Women had already spent a century fighting for agency. It didn’t seem particularly revolutionary itself.

Revolutionary Girl Utena is all about prisons. Coffins, and relationships and schools that we wrap around ourselves to keep us from having to deal with the real world. Literal floating coffins populate the movie manga. Utena herself is found by Touga as a child laying in coffin in a church…and of course, Ohtori itself is presented in the shape of a keyhole Kofun tomb.

And the fairytale comes with a Greek chorus. The Shadow Girls provide commentary, gossip, insight and Macguffins in the form of news “extras.” Relevant, irrelevant, digression, derailment and diversion, they all ended up being meaningful…even the bits that made no sense.

The animation, like the writing, is full of references and homages to classic anime. Shades of Ryoko Ikeda’s Rose of Versailles and Oniisama E fill every space of the visual text and subtext when Arisugawa Juri (who looks like Miya-sama, but loves like Saint-Juste) and Utena duel for the Rose Bride.

Symbols with no meaning, or fungible meaning, populate Ohtori. Invisible baseball games and trains punctuate Student Council meetings and animals take on a darker aspect when they show up merely to harass a single character. Symbols are frequently ambiguous, until they are the most straightforward of allegories: Utena as a car is literally the vehicle that Anthy uses to escape Ohtori.

The animation is unusual, the character designs classical, the symbolism is surreal. And all of it is thrown together over a soundtrack that is it’s own character.

The music in Utena was once described to me as being “like a magical cookbook on acid.” There’s a lot of truth in this. Terahara Takaaki, working under his professional name as J.A. Seazer, set the duels to staccato-beat-backed rhythms, punctuated by lyrics that list metaphysical terms in an almost alchemical formula. The music can’t be ignored, and, indeed, is one of the defining characteristics of the anime. “Zettai Unmei Mokushiroku” is used in the television anime as the background to the weekly transformation scene and is the background for the even more extraordinary transformation of the movie, where “Rinbu Revolution,” which was the opening theme of the television series becomes the final race to freedom in the movie in what is an extraordinarily epic scene.

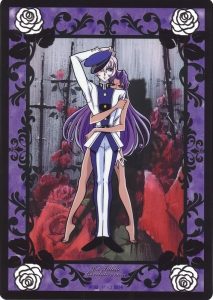

And then there was the sexuality of the characters. The online fandom was both stimulated and inspired by anime characters who appeared to be homo- or bisexual…or, in the case of Akio in the anime particularly, probably pansexual. The manga was more strictly heterosexual, but it still crossed lines of propriety. Not nearly as much as the anime in which we are forced to recognize Akio’s predilection for sexual abuse, incest, rape and generally using sex as a weapon against what we must understand to be underage characters. And how uncomfortable we all felt about that…even as people wrote fanfic of it. Sensuality and sexuality are presented as part and parcel of the characters’ interactions with one another in almost all the versions of the story.

The Story of a Revolution Seen Through Five Lenses

Tenjou Utena almost died as a young girl in an accident that killed her parents. A prince saved her. He kissed away her tears and gave her a ring. Keep your nobility, he told her, and it will bring us together. She decides that she, too, will become a Prince. At Ohtori Academy, this desire to be a Prince drives her to save a girl from being hurt by a boy and Utena ends up dueling the boy for the Rose Bride.

Tenjou Utena almost died as a young girl in an accident that killed her parents. A prince saved her. He kissed away her tears and gave her a ring. Keep your nobility, he told her, and it will bring us together. She decides that she, too, will become a Prince. At Ohtori Academy, this desire to be a Prince drives her to save a girl from being hurt by a boy and Utena ends up dueling the boy for the Rose Bride.

The television anime series used a palette of bright colors over an almost drab world. The Student Council uniforms were military-informed, but color-coded to the character. As if we were being told that each member of the council was wholly unique and their position was not reproducible, it would disappear with them. The story does nothing to dissuade the viewer of that belief. The Council each carry a deep psychic wound of some kind. As adults it’s not hard to understand that it is the wound that is the specific quality that makes the character attractive to Akio. The nature of the wound and the way that wound allows him to manipulate the character is the driving force of both the television anime and the manga. Utena is presented as different from everyone else in the school, and different from the Student Council members, but is not incorruptible.

Tenjou Utena has been receiving postcards from “her Prince” every year on her birthday. Although she lives with her aunt, she is always looking for that apparently imaginary prince. When she realizes that the postcards form a photo of a location, she transfers to Ohtori Academy in order to find her prince. She finds that the ring she wears leads her into dueling for the Rose Bride.

The television manga was as much about symbols of life and death as the anime, but the symbols lingered, heavier in their presence. Duels leading to coffins is not nearly as surreal as an invisible baseball game punctuating a fraught conversation, it’s more straightforward. The manga is more heterosexual, with less overt sexuality than the anime. But the coming-of-age fairytale remains centered around Utena, giving up looking for her prince, but never giving up on her own princeliness…and Anthy, the princess unable to even ask for rescue. It’s a simpler tale, for less mature audience than the anime, but the end moment has the same weight in both television anime and manga – the end of one epic and the beginning of another.

***

Enjoy today’s post? Subscribe to Okazu with Patreon!

***

Utena has come to Ohtori Academy to look for her Prince, Touga. She sees him, but is unable to get close to him. She is drawn into duels with the Student Council and learns the secret of the Rose Bride. Together, she and the Rose Bride attempt to escape Ohtori.

The Adolescence of Utena movie came at the end of the 1990’s, as anime was hitting a new peak of popularity in the United States.

The film was released in English with some fanfare – the director, Ikuhara himself, came to speak about it to fans and press, sponsored by Central Park Media, the company that had licensed it. The film was even shown at several Gay and Lesbian Film Festivals in the beginning of the 21st century. The movie took the basic elements of the plot, reshuffled them, and gave it a more – to western eyes, at least – overtly lesbian ending. The scale of the movie was…large. Vistas of the movie Ohtori needed the 70 millimeter film screenings to be properly seen. The school itself had been broken apart, with shifting pieces in real time; buildings and chalkboards, and the dueling ground – all stained with blood-red shadows – move around the characters, never still. The dueling ground itself is impossibly perched high above the school. The floating castle looms even larger and more menacingly than it ever has; not as a goal, as it was in the television anime, but as an enormous obstacle capable of crushing dreams flat.

The music was remixed and re-used in ways that didn’t contradict the original, so much as make it even more of a palpable presence in the story. “Rinbu Revolution” remained a song of defiance, but whose? In the television anime, one would assume it belonged to Utena, where in the movie, there’s no doubt at all that it is Anthy’s theme.

Utena comes to Ohtori to find her lost Prince and ends up dueling the Student Council in duels that center around the Rose Bride. But Ohtori is not what it seems. It is a tomb…and always has been. Utena and Anthy find their way out together.

Utena comes to Ohtori to find her lost Prince and ends up dueling the Student Council in duels that center around the Rose Bride. But Ohtori is not what it seems. It is a tomb…and always has been. Utena and Anthy find their way out together.

The movie manga reshuffled the characters again, playing up the sexuality and the life and death refrain once more, but it ends with a scene borrowed from early 20th century Japanese girl’s literature, Yoshiya Nobuko’s Yaneura, no Nishojo, when Anthy offers her hand to Utena and say, “let’s go outside.”

In both the television anime and manga, the end comes with Utena’s disappearance and Anthy leaving Ohtori to go find her. She doesn’t explain to her brother in the anime, because Anthy can see that Akio is trapped in his own game. In the television manga, Touga is the person to whom she explains.

“I…I have to go.”

“Go where?”

“To look for Lady Utena. When she and I meet once again…that is when this will begin.

The world…awaits the Power of Dios…

And that power begins with us…!”

20 years later, Touga has mostly forgotten this story. In the 20th anniversary manga, published in 2017, he and Saionji meet up and are invited to return to Ohtori. In the chairman’s rooms, their memories of Utena and Anthy are rekindled. But where – if anywhere – it will lead, we don’t yet know. The 20th anniversary manga is so far a single chapter, with a second chapter to come. Whether Touga, Saionji, Juri or Miki, or we, will ever see Utena and Anthy again is still unknown.

Utena’s princeliness, persistence and “nobility” weren’t the revolution. They were the catalysts that created the revolution. In anime, manga, television and movie, it becomes apparent that Utena is the power to grant the revolution.

Whether to look for Utena, to literally drive car-Utena or to walk hand in hand together, it becomes clear that the revolution itself is, in every version, the moment Anthy walks away from Ohtori. Only Utena had the ability to grant Anthy that power; the ability to leave the coffin of adolescence and enter the outside world.

Along with being a subversion of magical girl series in general it is easy to see Revolutionary Girl Utena as a subversion of every school drama every in anime and manga – and of adolescence itself.

Revolutionary Girl Utena Manga Deluxe Set is available from Viz Media.

Revolutionary Girl Utena Anime and Adolescence of Utena Movie are available from Nozomi/Rightstuff.

![]() As I read Nakatani Nio’s Bloom Into You, Volume 3, I get to experience a vast range of emotion, much of which I find hard to put into words. I can’t help seeing the narrative through my own lens, even when the characters tell me that my interpretation is wrong. ^_^;

As I read Nakatani Nio’s Bloom Into You, Volume 3, I get to experience a vast range of emotion, much of which I find hard to put into words. I can’t help seeing the narrative through my own lens, even when the characters tell me that my interpretation is wrong. ^_^;